AI Made Me Do It

12 Jun 2025 - Cooper Hopkin

Sometimes, I almost wish things were more difficult. That way, when I personally make things way more difficult than I need to, at least I could have an excuse.

You see, the problem with me (okay, one of the problems with me) is that I tend to make what should be fairly simple tasks way more difficult than they actually need to be. My homelab is a pretty good example, actually. I started with a TPLink router, a Raspberry Pi, and a dream. That quickly became two (sorry, make that three) Raspberry Pis, an Intel NUC, a NAS, several other peices of networking equipment that I probably can’t afford, and a sprawling network infrastructure that I would need to draw out in crayon in order to make it make sense. At least in this case, it’s okay that it’s complicated. It’s a homelab, that’s the point. I can make it as simple or as complicated as I want.

Where the problem really kicks in is when I try to actually do the things that I’m wanting to do in my homelab.

I’ll take the ELK stack for example, because that’s what I’m working on as I write this post. Elastic (the company that actually makes the components of the ELK stack) actually makes it pretty easy to set everything up. But there are two problems. First, the documentation is kind of a hot mess (at least for my purpopses). Not nearly as bad as some other things I’ve seen, but the issue with this documentation is that Elastic is a corporation. Their product itself is free and available for everyone to use. But they have to make money somehow, so they offer several different managed solutions of some sort or another. Plus, the ELK stack is really geared towards enterprises who need full scalability, high availability, and security procedures that I simply don’t need to worry about in my home lab. But because there’s only one set of documentation, the information I need to get up and running is mixed in with all of the stuff that enterprise-level users need to worry about, with some up-selling for the managed solutions sprinkled in. So trying to figure out what I do and don’t need, then picking out the stuff I don’t have to worry about because I’m not building out an entrprise-level SOC, can be a bit difficult.

The second problem is, of course, me.

I make everything more difficult than it needed to be. Throw me at a simple problem, and I’ll take 3 hours debugging an issue that I introduced myself while in the process of making the simple problem more difficult. Even just writing this blog post, I spent an ungodly amount of time trying to get that stupid picture of an elk to look and position itself correctly, all for a joke that isn’t that funny (to others at least. I think it’s hilarious). I can tell myself that I’m saving time for the next time I want to put an inline captioned photo in a blog post, and in that specific case, maybe I’m right. But the point is that I introduced that problem myself, and spent more time fixing the self-inflicted issue than I probably would’ve spent writing the rest of this post.

In the case of ELK stack, it wasn’t so much an issue I introduced into the project, but rather how I went about starting the project. See, I’ve had a couple of interviews in the past few months (yay!), and in both interviews they asked “What are your thoughts on AI?” And I realized, I don’t really have much more than theoretical opinions, because I’ve never really used AI. I was finishing school basically right as AI started becoming “smart” enough to use to help with school tasks, and I didn’t really have anything at work that required any interaction with AI. So I kinda just… never used it. When I ran into a roadblock or problem, my first thought was always “Crap, time for a bunch of googling” and not “Let’s go ask ChatGPT about its opinions on Ukrainian geopolitics.” I started this part of my project, and thought “Hey, all of these recruiters are asking me about AI, let’s try actually using it.” And that’s been… Good and bad. I’ve realized that ChatGPT is really good for the beginning stages of planning and to give you a good starting point in solving a problem. However, you really, really shouldn’t blindly follow step-by-step instructions on how to build a highly integrated tech stack on a Proxmox VM for observing a poorly laid out network infrastructure.

Let me explain.

I wanted to implement some threat monitoring and infrastructure observability to my homelab. I learned about SecurityOnion in school (or it was at least mentioned), so I decided to go with that. I spun it up, saw how many resources it was eating up, turned it off, and deleted it. Then I remembered that SecurityOnion is based on the ELK stack (Elasticsearch, Kibana, and Logstash, for those who don’t know), it just has a ton of extra features. I don’t really need those bells and whistles, so I figured I’d spin up a VM with a basic ELK stack implementation and Suricata instance and save a solid ~8 GB of RAM. That’s all I really need. I probably don’t even need Logstash, if I decide I don’t need the data pipelining. So I went to ChatGPT, and I said, “Hey, I want a lightweight alternative to SecurityOnion, using the ELK stack.” And it it said “Okay! Do this list of things!” And I did. Or at least, I tried to. The instructions at the very beginning were okay, but as I went along the instructions got worse and worse, and I started to need to go to the documentation to actually do the things it was telling me to do, which made it more confusing, because the documentation kept referencing things that I hadn’t done or hadn’t been told to do. Eventually it got bad enough that I said “screw it, I’m doing this myself.” So I nuked the VM, spun up a new one, and actually went to the start of documentation where it tells you things like prerequisites, system requirements, and, most importantly, the order in which the stack components should be installed to avoid missing dependencies.

The AI didn’t even get the installation order right.

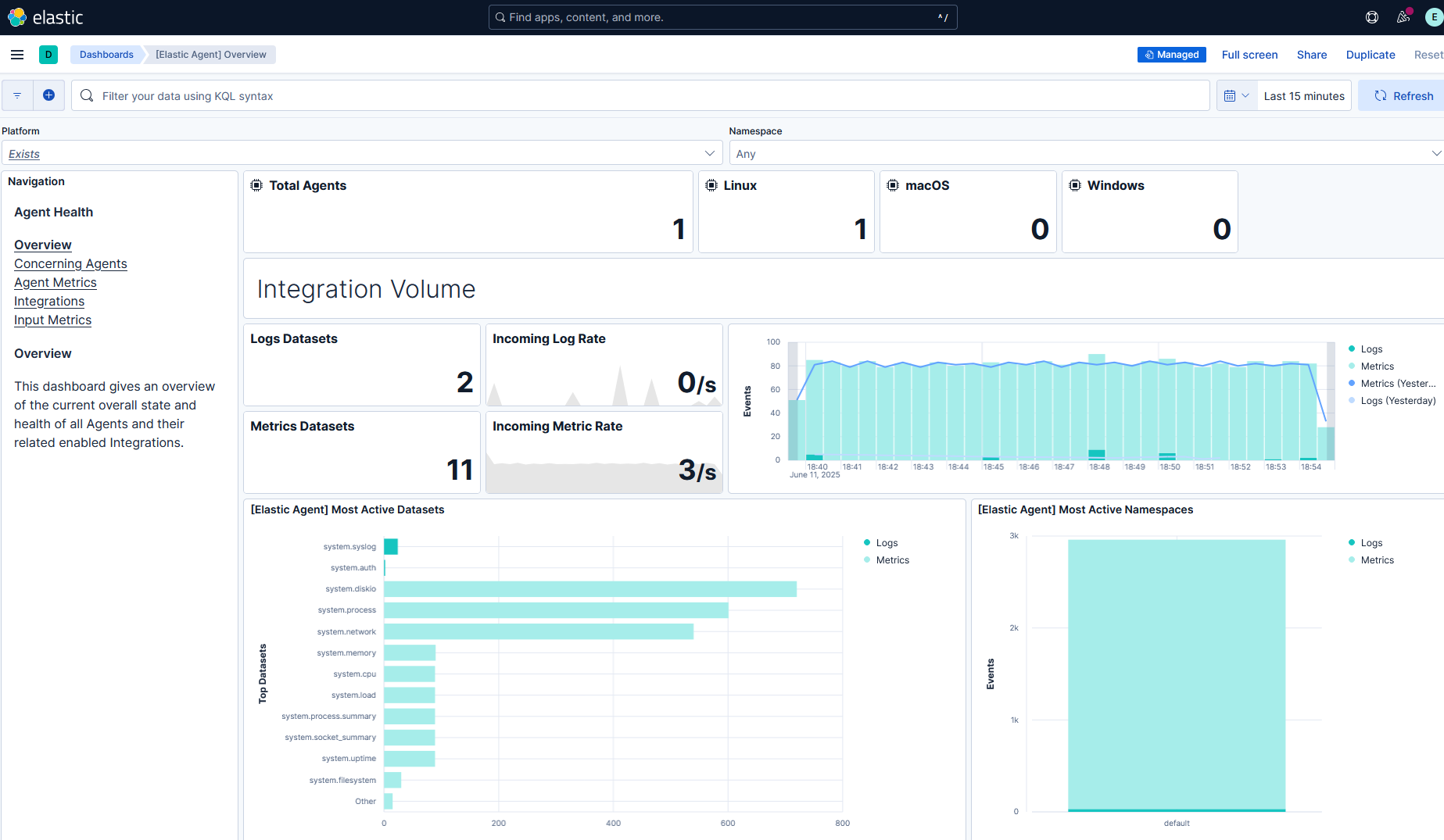

Don’t get me wrong, it was still confusing (read above: hot mess documentation), but at least I was actually getting it to work. Data was flowing in, visualization was (mostly) working, and I was able to start deploying agents to collect data. I haven’t really even gotten beyond that part yet. There’s still more I need to do, and I haven’t even scratched the surface of what’s possible with the tech stack I’m working with. But it’s working, it looks pretty, and I can pretend like I know what I’m doing.

The funny thing is, for all of the ranting I’m doing about AI, documentation, and my own deficits, I’m actually glad this all happened! I learned a lot of stuff about a lot of stuff. First and foremost being a lesson about what generative AI should and should not be used for. But I made a ton of mistakes in an environment where it didn’t really matter if I screwed things up (so second lesson was about the purpose of a test environment, I guess). Through those mistakes, I learned a lot of things that I probably wouldn’t have even considered had everything gone correctly. That’s kind of been my experience with a lot of my homelab, actually. Trial, error, and the occasional “Why can’t I reach the internet? Oh, yeah, DNS.”

I guess what I’m saying is: go and make some mistakes (preferably in a testing environment). Make mistakes, figure out what went wrong, READ THE DOCUMENTATION, and then fix the mistakes. Rinse and repeat. You’ll learn a lot more doing that than if you followed a guide and everything just worked. Make sure that you’re actually understanding what you’re doing and why you’re doing it. And you don’t even need to have an end goal if you don’t want to! You can just follow the flow of the project. I started this project by trying to install SecurityOnion, and ended (or at least, got to this point) with figuring out how to put a picture of an elk inline with a paragraph and give it a caption. On a blog. As a joke. Just follow where the flow takes you.

So yeah. Go make mistakes. Because the funny thing about mistakes is, if you do it right, making mistakes leads to fewer mistakes in the future.

–Cooper

P.S. If anyone was curious, the right order to install the ELK stack is Elasticsearch -> Kibana -> Logstash -> Client services (Elastic Agents, Beats, APM, etc)

Hello World in Brainf*ck

[

Brainf*ck is an esoteric programming language that essentially

emulates a turing machine. You have cells that contain 1-byte

values. > moves to the next cell, < moves to the previous cell,

+ increments the value, - decrements the value, . outputs the

ASCII encoded value of the current cell, "," accepts one byte

of ASCII encoded input and stores it in the current cell. If the

current cell is 0, "[" will cause the instruction pointer to jump

to the matching "]" command, and after a "[" instruction, if the byte

in the current cell is non-zero, ] will jump back to the matching

[ command.

This whole thing is an initial comment loop in brainf*ck. Because the data

pointer at the beginning of a program is always 0, when the compiler

sees the "[" at the beginning of the instruction set, it will

immediately jump to the matching "]" instruction. Be careful,

because anytime you use a "[" in the initial comment loop, the

loop still has to be balanced with a corresponding "]" instruction.

This program should print out Hello World. I hope. ]]

++++ ++++ Set C0 to 8

[

> ++++ Add 4 to C1; This will always set C1 to 4

[ Because the cell will be reset with each loop

>++ Add 2 to C2

>+++ Add 3 to C3

>+++ Add 3 to C4

>+ Add 1 to C5

<<<<- Decrement loop counter in C1

] Keep going until C1 is 0; 4 loops

>+ Add 1 to C2

>+ Add 1 to C3

>- Subtract 1 from C4

>>+ Add 1 to cell 6

[<] Move to the first cell containing 0 you find; should be C1

<- Decrement loop counter in C0

]

>>. C2 contains 72 which is H

>---. Subtract 3 from C3 to get 101 which is e; print

++++ +++.. Add 7 to C3 to get 108 which is l; print

+++. Add 3 to C3 get 111 which is o; print

>>. C5 = 32 which is " "; print

<-. Subtract 1 from C4 to get 87 which is W; print

<. C3 = 111 which is o; print

+++. Add 3 to C3 to get 114 which is r; print

---- --. Subtract 6 from C3 to get 108 which is l; print

---- ----. Subtract 8 from C3 to get 100 which is d; print

>>+ Add 1 to C5 to get 33 which is !; print

>++. C6 = 10 which is newline; print